An excerpt from the upcoming book by Armando Nieto, Mary Conrad, and Matt Pallamary: The Santa Barbara Writers Conference Scrapbook — Words of Wisdom from Thirty Years of Literary Excellence 1973 – 2003

On Thursday night at the 1989 SBWC, Charles Champlin, The Movies Grow Up—1940-80 and Back There Where the Past Was, long time editor at the Los Angeles Times and beloved SBWC workshop leader was billed as the featured speaker in the SBWC mailings, but decided to share the stage with Joseph Wambaugh, author of The Onion Field, The New Centurians, Echoes in the Darkness, etc., a late addition to the Conference.

Barnaby said in his introduction, Chuck Champlin coined the phrase “I love this conference. Its become the punctuation of my life.” Champlin himself endorsed the phrase when he spoke, talking about the aloneness of writing. He said his endorsement of the SBWC was heartfelt because at this stage of his life, he valued the authenticity and craft of writing, and the opportunity to rub shoulders with fellow spirits.

Champlin spoke in a homespun singsong voice reminiscent of Garrison Keillor and A Prairie Home Companion, bringing alive a time when telephone numbers were WJ5, and bicycles were the main form of transportation around town.

He finished his remarks saying, “I wish you ongoing success with your compulsions, which I share.”

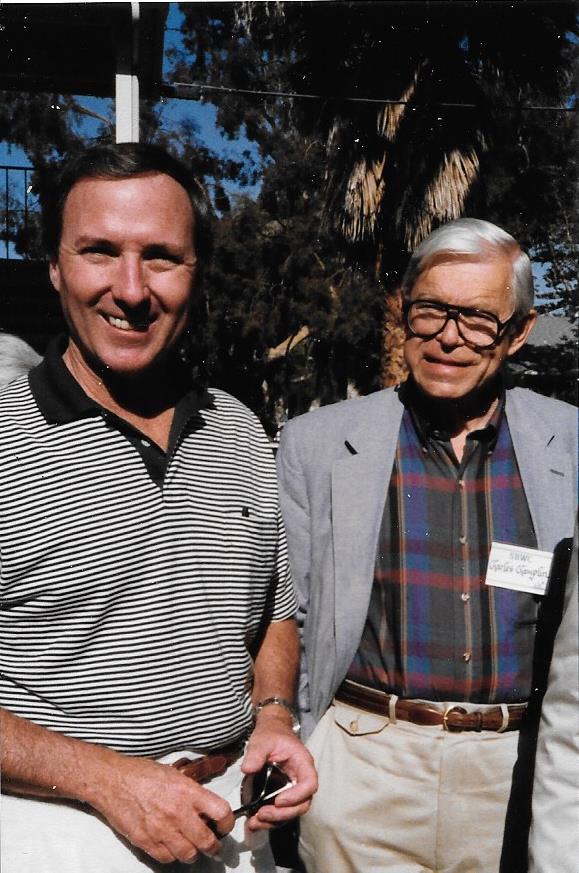

Joe Wambaugh and Chuck Champlin

In his introduction of Joseph Wambaugh, Barnaby Conrad said Wambaugh was quoted as saying “All my wrinkles are on the inside,” in response to a lady’s flattery, and why not, as he was a veteran of fourteen years on the Los Angeles police force.

A special treat for the audience, Wambaugh’s “lecture” took the form of being interviewed by Barnaby Conrad and questions from the audience. For his part, Barny asked how and why Wambaugh wrote alternately fiction and non-fiction.

“Because I can’t always come up with a fiction idea,” he said, Wambaugh sometimes wrote “true crime” stories. Another benefit of writing non-fiction was his comfort level with stumping for those works.

“I was able to publicize The Blooding: The True Story of the Narborough Village Murders,” he said, “because it was a true story, and I wasn’t promoting my own idea.” It was the first time one of his books had been publicized in years.

“When I write a novel, a lot of things change, I go back and forth with my editor,” he continued. Not so much with non-fiction.

Regarding the movies made from his works, he said, “the only one I didn’t like was The Choir Boys. It was a rotten, lousy, sleazy, disgusting movie.” Perhaps it was this kind of attitude that contributed to his reputation among some in Hollywood, but he said he was a much more mature and sober man these days.

Writing for Wambaugh was a means to express a creative energy that plagued him in his adult life. He began with short stories sent to magazines that would pay a penny a word. One story he even sent off to Playboy twice over the space of a year.

“And some cruel bastard at Playboy sent it back, writing, ‘Its no better this time than it was the last!’”

He said that writing while working as a policeman was something he never talked about at work, “and my short stories never sold, to this day!” He also said he believes his first novels were clumsy and somewhat amateurish, perhaps because he first wrote novels as a moonlighting cop—in his mind. Instead of as a writer should write.

He couldn’t say enough about his editor, someone who he’s worked with since The Onion Field. “If you are lucky enough to have an editor, never let her go.” He credits his editor as half the reason for his success in writing subsequent novels.

The other half of his success he attributes to leaving the LAPD.

Barnaby Conrad and Joseph Wambaugh